Welcome to Band Jury, a SPIN series in which artists defend black sheep albums they feel deserve another listen. These are projects that, for whatever reason (middling sales, negative reviews, a misunderstood stylistic shift), have fallen slightly out of fashion—or perhaps never reached it to begin with.

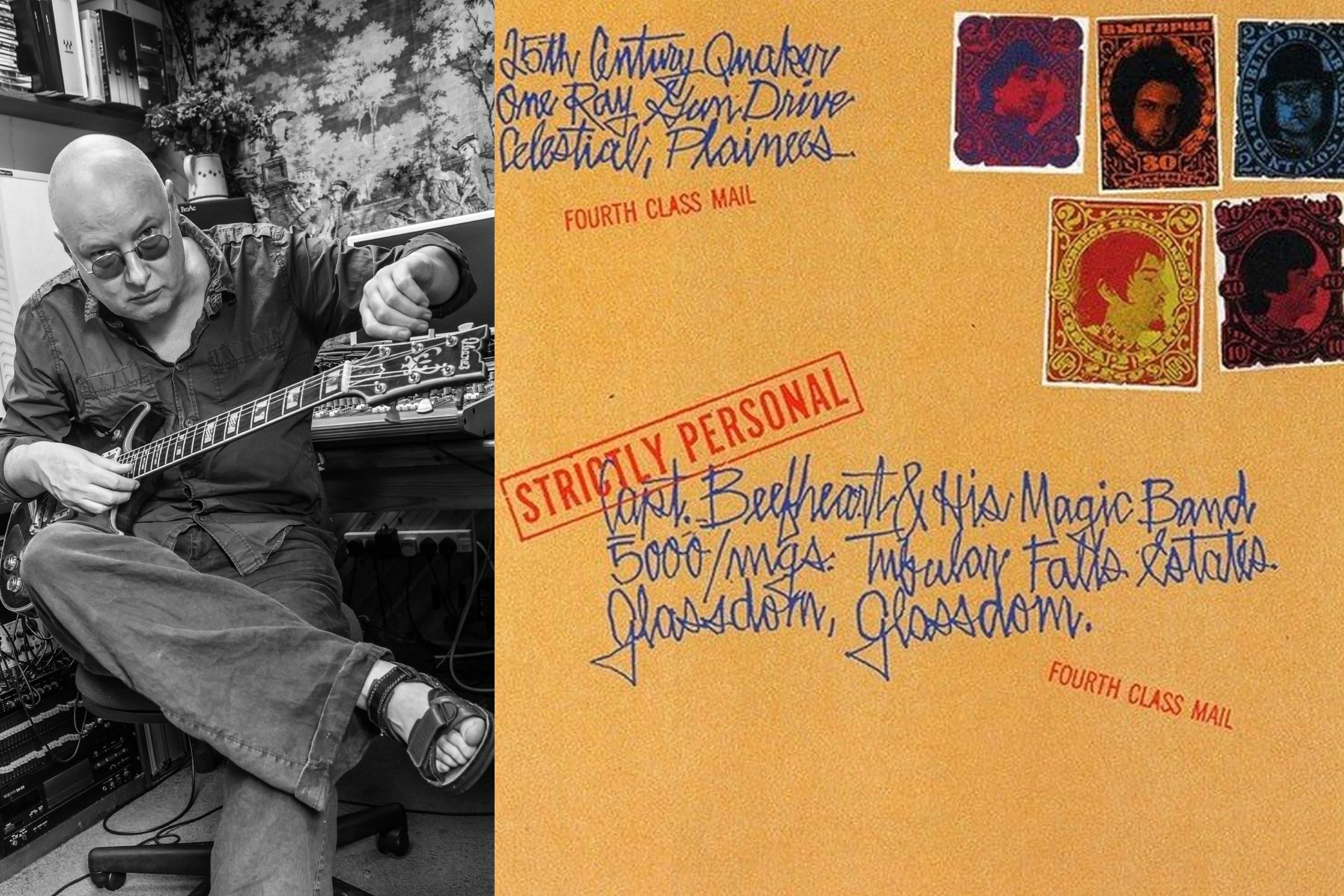

The Defender: Andy Partridge

Qualifications: Singer/songwriter/guitarist/producer, best known for his work in the innovative British art-pop band XTC; recently released the art book Popartery and a reissue of XTC’s 1984 album, The Big Express; human who enjoys music

The Defended: Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band’s 1968 album, Strictly Personal

Overview: A contemporary Rolling Stone review proclaims that grooves of “pure Delta gold” are marred by lapses “into dull commercial rock on the order of noisy, discom-bobulated freakout shit.” A retrospective AllMusic take is more complementary. On fan-review site RateYourMusic, it ranks ninth (a still-solid 3.42/5.0) of the 12 Beefheart studio albums.

Andy Partridge is here to discuss the musical genius of Captain Beefheart—an assignment he hasn’t taken lightly.

The XTC co-founder is armed with tools: an array of web links (a photo of John Lennon sitting in front of some Beefheart stickers), deep-dive factoids (details about wacky album-art photo shoots)—even his unplugged Ibanez Artist electric guitar, which he uses at one point to demonstrate a riff. “I can’t hear too much Beefheart,” he says, detailing an enthusiasm that dates back decades. “It’s like a really strong alcoholic drink. I can’t have too much of it, and I love it dearly.”

You might not hear Partridge’s music—which has evolved gracefully from early post-punk and New Wave through progressive- and psychedelic pop—and naturally think, “Big Beefheart fan.” But it makes a certain sense: Both XTC and Beefheart recorded subversive, experimental music—the former’s just happened to involve a lot more dizzying melody, and the latter’s a lot more knotty blues and absurdist poetry.

Beefheart built a rabid cult following with an abrasive style that’s tough to pigeonhole (and, for the faint of heart, tough to comfortably sit through). But his second album, 1968’s Strictly Personal, is rarely mentioned in the same breath alongside avant staples like Trout Mask Replica and Lick My Decals Off, Baby. Perhaps part of the reason is that Beefheart, during interviews, famously criticized the album’s divisive, era-specific production. That’s Partridge’s main theory anyway: “I think [he] himself had a lot to do with shooting himself in the foot there.”

The XTC legend outlined to SPIN his entire Beefheart fandom: first hearing the music as a kid, becoming obsessed, covering a song onstage, separating art from artist (“Did you ever read the book that [drummer] John French wrote? Be careful—it’s a kick in the balls for any Beefheart fan”), and, crucially, why he believes Strictly Personal endures.

Do you remember the first time you heard Captain Beefheart?

I can tell you exactly the first Beefheart record I heard—I heard it through a wall. I was at that age, just kind of finishing off being a kid and just starting to get interested in girls, and after school I’d go ’round to my best friend [David]’s house. He’d say, “I got this new Dinky truck” or whatever. I’d think, “I feel guilty for liking these toys. I should be getting out of this now.” I’d hear this strange music coming through the walls because his older brother, who was, say, three years older, was in the next bedroom. And he was playing the Safe as Milk album. I thought, “What is that strange music? That’s really intriguing!” After a while I found out what it was—the older brother said, “What are you listening up my door for?” “Oh, I really like the sound of that music.” “Here it is, if you’re interested.” Of course, I couldn’t afford records. So I said, “When I get some music, I’m gonna get that.” That was my first hearing of Beefheart—I enjoyed the otherness of it. I didn’t hear Strictly Personal [next]. The next time I heard Beefheart, a very good friend of mine who was responsible for turning me on to a lot of strange music, said, “You’re going to hate this [Trout Mask Replica]. But stick with it—it will click. You will learn to love this.” I think I loaned him whatever I had at the time—probably a Monkees album or something.

What a trade!

Yeah! I put on Trout Mask Replica, and I’m thinking that [typical] thing: “They’re out of tune. They’re out of time. He’s not singing—he’s just yelling.” I didn’t get it in any way. I said to [my friend], “Look, Spud—seriously, man. I can’t get on with this. You’ve gotta take it back.” “No, stick with it.” I had it for probably six weeks or more, trying it every day. Then something just happened. It went bing! “This is the best thing I’ve ever heard in my life! They’re not playing out of time–that’s the time they’re keeping! Oh, he’s playing that part, and it goes against—or rubs great—against the part he’s doing! He’s just yelling this poetry—it’s great poetry—over the top!” I had a red exercise book, and I’d sit for hours, a line at a time, and try to work out what Beefheart was singing. I didn’t get a lot of it because they were American cultural references–things like “my Speidel wrist around my honey.” I didn’t know Speidel made watch straps. I kept saying, “What’s he saying? He spied something?” We never got the lyrics with the British release. I had to fill up this exercise book.

That was exactly my experience. I bought a CD reissue as a teenager, and I was fascinated by all of it: the album cover, the title, the glowing reviews I’d read. But I absolutely hated it. I kept trying and trying, and eventually it clicked. I’m still trying to convince my wife, though.

[Play Trout Mask Replica] if you want to kill a party or drive all females from a room!

I’ve never talked to anyone who’s mentioned Strictly Personal in conversation. It definitely doesn’t get the same amount of respect as, say, Trout Mask Replica. Most interestingly, though, Don Van Vliet—Beefheart himself—distanced himself from it. What do you make of the album’s reputation?

When the album came out, he more or less immediately disowned it, saying it’s covered in—what was the phrase—“psychedelic Bromo-Seltzer”! Hey, to me, that’s more of a fishing lure [than a negative]! I’m going to bite that line if people are calling it “too psychedelic.” I’m going to check that out. You know the story of the album, don’t you? It was [intended to be] a double-album, and they planned to call it It Comes to You in a Plain Brown Wrapper, which is why it was going to be a gatefold, like an envelope with porn magazines or whatever inside.

The big hangup for Beefheart seems to have been the production of Bob Krasnow, including the heavy use of era-specific phaser effects. “That’s the reason that album is as bad as it is,” Beefheart told Rolling Stone. “I don’t think it was the group’s fault. They really played their ass off—as much as they had to play off.”

Seriously, I think [the mixed reception] is him just saying it’s bad because of all the effects. People are going, “Oh, if even the good Captain doesn’t like it, I don’t think I’m gonna like it.” I think it’s head and shoulders above that stuff he did for Virgin: Unconditionally Guaranteed, Bluejeans & Moonbeams. They’re wretched! They’re terrible! But I was a big fan of Strictly Personal. I really like some of the choices of sounds and the way it’s edited. It’s not like an album of songs where each song is in its own little cupboard. Songs spill over into each other, or songs reprise again. Especially “Ah Feel Like Ahcid”—that reprises several times during the album. The whole thing is like a psychedelic film. I really like that.

I bought Mirror Man when it came out. That had several long jam pieces, like “25th Century Quaker,” which early XTC used to cover. [Laughs.] Possibly the first time [future XTC bandmate] Colin Moulding saw my band, we were either called Clark Kent—way before the Police drummer fella, Stewart Copeland—or Star Park. We were playing at Colin’s school, driving out the dozen or so people that were in the hall. Literally. And it was like, “Ah, fuck it, let’s play ’25th Century Quaker.’” Colin slid in with a friend of his and watched us on the back wall. He saw us struggling through that.

What are some of your favorite songs on Strictly Personal?

“Ah Feel Like Ahcid”—it’s not a concept album, but it’s like an improvisation around [Son House’s] “Death Letter Blues,” and he’s mixing in all this stuff about acid on stamps. “Beatle Bones ’n’ Smokin’ Stones” I like a lot because it’s filmic. But I really love “Trust Us,” which is like a sort of Chinese blues. There’s a lot of those Oriental things [demonstrates harmonies on guitar]—a lot of those intervals. I can’t hear too much Beefheart. It’s like a really strong alcoholic drink. I can’t have too much of it, and I love it dearly.