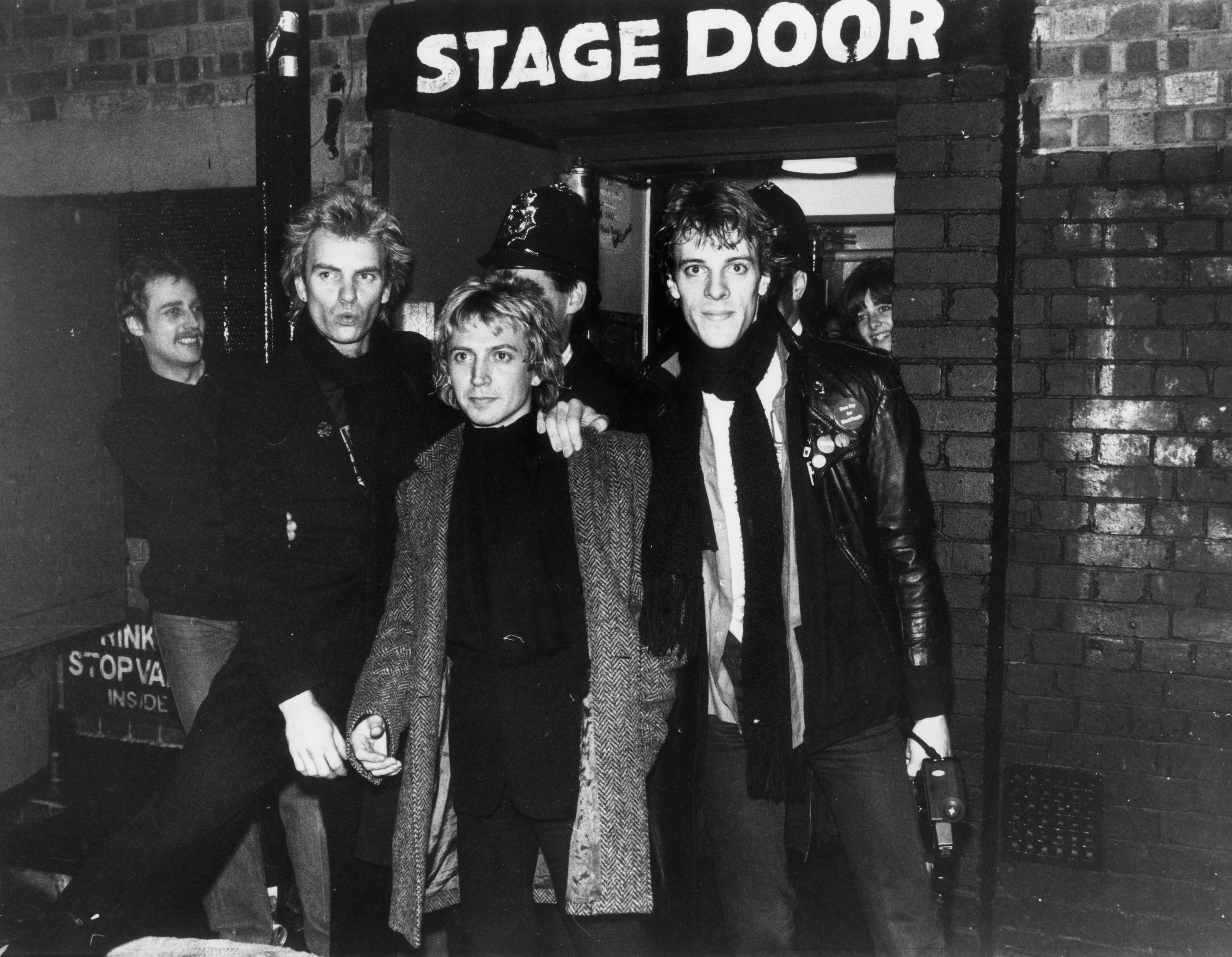

In 1977, vocalist/bassist Gordon “Sting” Sumner, guitarist Andy Summers and drummer Stewart Copeland were three talented but unheralded U.K. musicians attempting to carve out careers amid the momentous punk revolution led by the Sex Pistols, the Clash and the Damned. When they teamed up later that year as the Police after a series of chance encounters and a bleached-blonde makeover, they collectively found the purpose which had been so elusive on their own. In barely five years, they’d become the biggest band in the world, only to splinter apart at the absolute peak of their power and disappear for decades in a haze of ego clashes, name-calling, and creative differences.

They only released five studio albums, but there has never been anything quite like the Police before or since, because Sting, Summers, and Copeland are amongst the most unique musicians of their generations: Sting, the handsome, brooding aesthete and tenor-voiced bass guitar virtuoso who was as fond of quoting Vladimir Nabokov and Carl Jung as he was singing total drivel such as “de doo doo doo / de da da da”; Summers, nearly a decade older than his chums and a diminutive fretboard innovator capable of making his guitar sound like a dinosaur’s yelp one moment and a cacophony of urban noise the next; and Copeland, who grew up in Lebanon as the son of a CIA diplomat and whose wry wit was as crucial to the band’s essence as his commitment to their hi-hat- and bass drum-driven grooves.

The Police’s earliest music gave courtesy nods to the prevailing punk sounds of the moment, but by their 1978 debut, Outlandos D’Amour, the band had settled into a reggae-tinged, melodic rock milieu which they’d continually shape and evolve until their demise in the wake of 1983’s Synchronicity. Their jaw-dropping instrumental chops rarely got in the way of a killer melody and their larger-than-life personalities were perfectly suited for the nascent MTV — a combination that generated dozens of pop hits and made them singular figures in rock history.

In honor of the release of a new six-CD boxed set belatedly celebrating the 40th anniversary of Synchronicity, SPIN evaluates the merits of the band’s small but mighty catalog while simultaneously pining for a follow-up to their box office-busting 2007-2008 reunion. Hey, an ’80s boy can dream, can’t he?

5. Zenyatta Mondatta (1980)

Recorded in a feverish, four-week session followed immediately by a world tour, Zenyatta Mondatta is the sound of a band moving beyond their first era without a clear destination in sight. That’s OK though, because there’s a lot to love about the trio’s third album, from the smiling-through-the-pain vibes of the terribly groovy “When the World Is Running Down, You Make the Best of What’s Still Around” to the terse, air-guitar worthy “Driven To Tears,” one of Sting’s first overt political statements about the brutal inequalities of a world motivated by greed. The cautionary tale “Don’t Stand So Close To Me” was inspired by Sting’s real-life experiences as a teacher barely older than his apparently amorous students, and the literal nonsense of “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da” is the band at their most lovably silly (they were both top 10 U.S. pop hits — the Police’s first). However, there’s little reason to endure the grating Summers instrumental “Behind My Camel,” and Sting clearly thought so little of this take of “Shadows in the Rain” that he later re-recorded it as a jazz/pop trifle for his debut solo album five years later.

4. Ghost in the Machine (1981)

The raw feel of Zenyatta quickly gave way to a dark, synthesizer-fueled patina on Ghost in the Machine, which contains such instant classics as the opening trifecta of the all-upstroke “Spirits in the Material World,” the preposterously catchy “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” (a No. 3 U.S. pop hit) and “Invisible Sun,” which thoughtfully ponders hope amid despair. To the chagrin of his bandmates, Sting wrote “Spirits” on his own on a Casio keyboard, and came to the sessions with a full demo of “Every Little Thing” featuring piano by Mauritian musician Jean Roussel. Unsure of how to replicate and/or better what was already on tape, Summers and Copeland simply overdubbed their parts onto the latter, ensuring it could never be performed live in a style faithful to the studio version and neutering this titanic rhythm section as ordinary sidemen fulfilling Sting’s widening pop ambitions. Your tolerance for a whole lot of rock’n’roll saxophone will dictate your feelings about “Hungry for You” (inexplicably sung in both French and English) and the zig-zagging riff-fest “Demolition Man,” but don’t sleep on the thrumming “Omegaman” or “Secret Journey,” which are two of the band’s better non-singles from an era where they were seemingly becoming more and more popular by the day.

3. Reggatta de Blanc (1979)

The Police ascended to quick stardom at home after their 1978 debut, but they exhausted most of their material during those sessions and didn’t have a lot to work with upon returning to the U.K.’s Surrey Sound studio to assemble their sophomore project. The solution? Pull bits and pieces from Sting, Summers, and Copeland’s collective back catalogs and turn them into something new — the lyrics for “Bring on the Night,” which weds Summers’ dexterous, flamenco-sounding acoustic guitar arpeggio to a strutting reggae grove, were nicked from a song Sting wrote for his prior band Last Exit, while “Does Everyone Stare” was built from something Copeland had written on piano while he was in college. Those material issues hardly matter when you can conjure songs as iconic as “Message in a Bottle” and “Walking on the Moon,” the instrumental components of which (Summers’ guitar line on the former, his ethereal “A Hard Day’s Night”-style opening chord in tandem with Sting’s bass melody on the latter) are as earworm-y as any vocal hook blasting out of a boombox at the turn of the decade. The trio’s signature instrumental interplay also shines on the wordless title track, a simmering groove built from a live jam that will likely inspire you to repeatedly jump up and down before it’s over. Fun fact: it won a Grammy for Best Rock Instrumental Performance. Take that, the Edge!

2. Outlandos d’Amour (1978)

Recorded in fits and starts across the first six months of 1978 before the Police had a record deal or any presence outside of grimy clubs in England and continental Europe, the band’s peppy, punky, irreverent debut album is loaded with superlative tunes. The first chorus of opener “Next To You” appears within 24 seconds, and from there, it’s the best Bob Marley rip three white musicians could reasonably get away with (“So Lonely”), a tango/rock mashup on which Sting reminds a French prostitute (“Roxanne”) that she doesn’t have to “sell her body to the night,” a sarcastic glimpse at how far a breakup can push a person (“Can’t Stand Losing You”) and even a song about the merits of synthetic human companionship (“Be My Girl – Sally,” with Summers providing cheeky, spoken-word narration). Sure, there’s some filler here in the form of the Rod Stewart-bashing “Peanuts” and the odd instrumental closer “Masoko Tango,” but as a template for how a band can successfully leapfrog anonymity en route to global fame, few albums have ever served as a better launchpad than this one.

1. Synchronicity (1983)

Quick: name another album of this or any other time inspired by the concept of coincidence which also went on to sell more than 10 million copies globally? Such was the rarified air the Police were breathing upon the release of Synchronicity, which is rightfully considered one of the best rock albums of all time. Although Sting and company could often barely tolerate being in the same room with one another at this point, their songs here are even better than ever. The oft-misunderstood “Every Breath You Take” became their first and only U.S. chart-topper and is arguably the biggest song of the 1980s, while “King of Pain,” “Wrapped Around Your Finger” and the bombastic “Synchronicity II” nudged the Police’s sound into more sophisticated, ear-pleasing realms. Opener “Synchronicity I” is one of the most unusual songs in the band’s repertoire, its 197-BPM Oberheim synth sequence racing across a litany of high-minded, science-themed rhymes (“logic so inflexible” / “causally connectible” / “nothing is invincible”). “O My God” and the drum-filled delight “Miss Gradenko” offer some final glimpses of the Police from an earlier, simpler form, and the evocative ballad “Tea in the Sahara” points the way toward the exploratory musical vibes of Sting’s early solo career. The less said about Summers’ shrill, incredibly unpleasant “Mother,” the better, as it is undoubtedly one of the worst songs ever included on an album of this quality. The just-released Super Deluxe Edition of the last Police album is a collector’s dream, as it sports 55 previously unheard demos (“Every Breath You Take” without guitar??), alternate versions and live cuts. Eeeee-ohhhh, indeed.