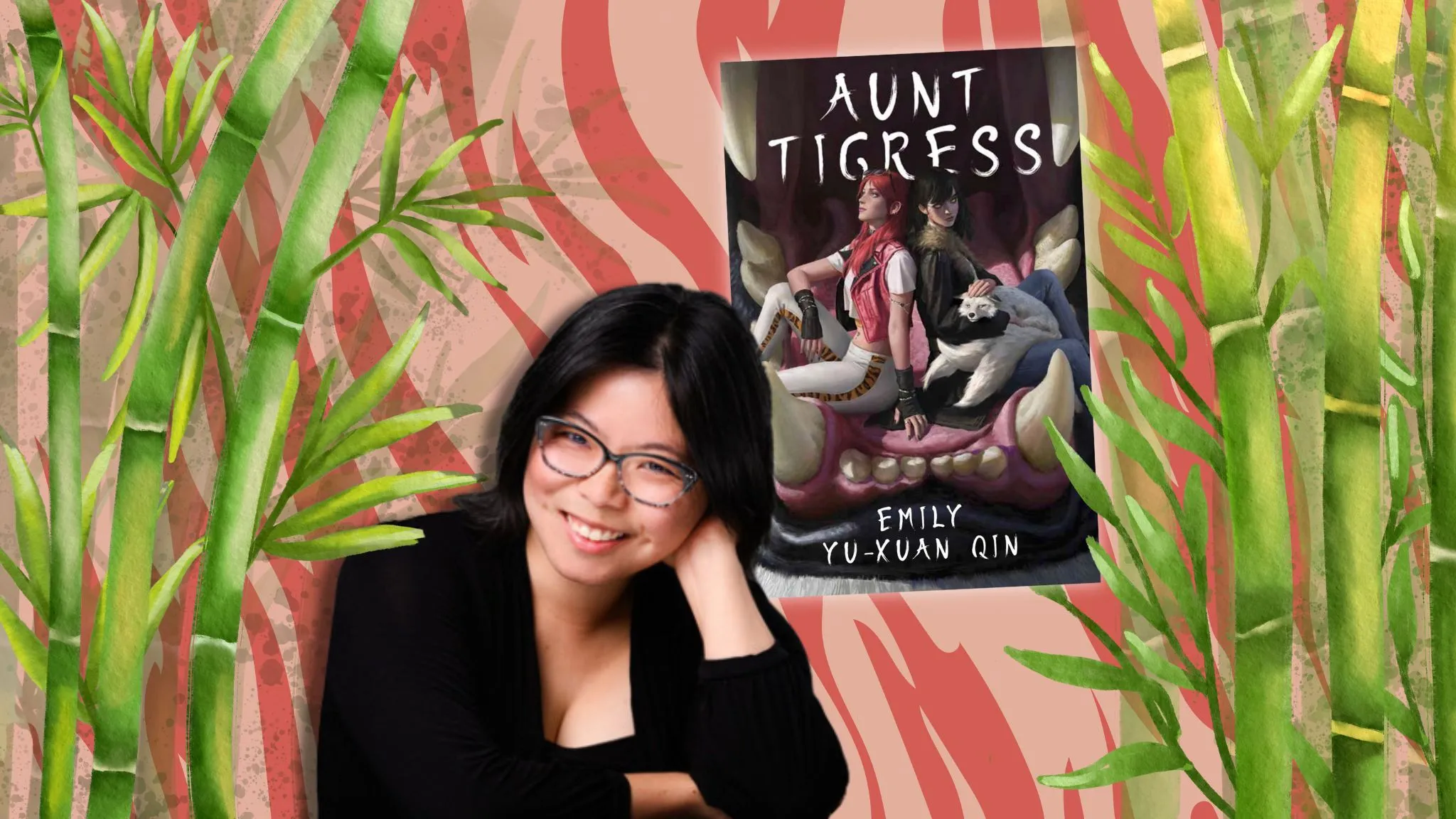

Emily Yu-Xuan Qin’s debut release, Aunt Tigress, is a snarky urban fantasy perfect for fans of Seanan McGuire, Ilona Andrews and Ben Aaronovitch. Inspired by Chinese and First Nation mythology and bursting with wit, compelling characters and LGBTQIA+ representation, readers will eat up this gory story — and the sweet-as-Canadian-maple-syrup sapphic romance at its monstrous heart.

DO MONSTERS DESERVE HAPPY ENDINGS?

Tam hasn’t eaten anyone in years.

She is now Mama’s soft-spoken, vegan daughter — everything dangerous about her is cut out. But when Tam’s estranged Aunt Tigress is found murdered and skinned, Tam inherits an undead fox in a shoebox and an ensemble of old enemies.

The demons, the ghosts, the gods running coffee shops by the river? Fine. The tentacled thing stalking Tam across the city? Absolutely not. And when Tam realizes the girl she’s falling in love with might be yet another loose end from her past? That’s just the brassy, beautiful cherry on top.

Because no matter how quietly she lives, Tam can’t hide from her voracious upbringing, nor the suffering she caused. As she navigates romance, redemption and the end of the world, she can’t help but wonder: Do monsters even deserve happy endings?

Check out what author Emily Yu-Xuan Qin has to say about writing these monstrous characters, intertwining a contemporary setting with mythology, and her experience as a debut author.

—

Aunt Tigress is a complex character, both monstrous and caring in her own way. Can you talk about what inspired you to create such a fascinating antagonist?

Aunt Tigress is an antithesis and natural extension of the prominent Chinese fiction genre and trope of cultivation, where characters seek to better themselves in body and mind through the pursuit of knowledge, power and immortality.

In line with Chinese mythologies, anything can cultivate themselves into a god — people, foxes, ghosts, a rock. Each being will have different methods of bettering themselves, and since the Taiwanese folktale of Aunt Tiger depicts a child-eater, my Aunt Tigress did the same.

When displaced to Canada, Tigress’s method of cultivation becomes an obsession with cultural theft and eating people. Cultivation, taken to an extreme, informs the most horrific aspect of Aunt Tigress’s personality — that she is driven and meticulously plans to eat other characters in the story.

Tigers are sometimes portrayed as dangerous in stories and media and, like many carnivores, are victims of misrepresentation that can complicate conservation efforts. They are usually only dangerous to humans when we don’t respect that they are wild animals.

When writing this novel, I remember a comment from my workshop group that suggested Tam’s tiger Father doesn’t act aggressive enough, and I responded that the portrayal of tigers as violent maneaters is a trope I’m actively working against.

Aunt Tigress, Tam and Father are the three tigers present in the novel and act as foils for each other. In Tam and Father, I wanted to portray the intrinsic fear of humans present in wild animals, the timidness and quiet of an ambush predator, and their explosive power when backed into corners. Aunt Tigress is the opposite; her persona is a patchwork of human, projected tiger traits and stolen identities. The details of which readers will find out.

Tell us about your publication journey as a debut author.

Aunt Tigress is my third manuscript. My road to publication was very long, and the last year or so has felt like a Cinderella dream. There’s still a lot of this journey left. I’m just hoping the shoe continues to fit.

My first manuscript was the thesis of my Master’s degree. Since then, I queried on and off to both agents and publishers while continuing to write. A lot of writing and several demoralizing years later, Aunt Tigress was written.

At the time, DAW was one of the only traditional publishers of fantasy that accepted unsolicited manuscripts, and my clumsy query and strangely specific story had little chance on paper. Yet, DAW’s Peter Stampfel pulled this very lucky manuscript from the slush pile. When I first received the email communicating interest from Betsy Wollheim, l had a rush of adrenaline that lasted maybe a week.

I was advised to search for an agent and was quickly brought back to reality … because it wasn’t easy. Not even with explicit mentions of an interested publisher. Almost a year later, Betsy, ever a champion and advocate, passed my manuscript to agent Matt Bialer, and that’s how it all started.

The rest of the journey was like hitching onto a train by my fingers — lots of waiting until we built momentum, and then a few months of whirlwind editing and developments I’m still out of breath from.

Aunt Tigress is set in modern-day Canada and is full of monstrous women and Chinese and First Nations mythology. What led you to choose a contemporary setting over a secondary world?

The first vignettes of Aunt Tigress were heavily influenced by the physical City of Calgary: the parks by the river, the winter grasses and especially the unpredictable swings of weather. Since Calgary is located on the traditional territories of the people of Treaty 7 and the Metis Nation, First Nations mythologies quickly became interwoven within the Chinese-based mythos of the novel.

And only after that did the novel’s central conflict emerge through the interactions of cultural research and emotion-motivated imagination. This novel asks what happens when very differently toned and themed mythologies — Chinese and First Nations — intersect and when those interactions imitate real-life oppressions. Since a specific urban setting was so intrinsically baked into the story, I’d never considered setting it anywhere else.

On top of the novel’s roots, many of the issues explored in the novel are contemporary. Searches for identity and place remain central issues for immigrants and ethnic minorities in Canada. Navigating the influences of parents and adult role models are lifelong, often therapy-assisted, endeavors.

Too many cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls plague multiple countries, and during the writing of Aunt Tigress, slews of gravesites of Indigenous children were uncovered on residential school sites in Canada. This novel helped me navigate the cultural grieving and my own strong feelings in light of these tragedies.

While few of these issues are new, our actions, choices and voices change and develop as societies transform. Aunt Tigress captures a snapshot of one little author and her attempts to navigate the contemporary world.

There are flashbacks and interludes peppered throughout the narrative that allow us glimpses into Tam’s childhood, before her decision to cut out her dangerous edges. They are some of my favorite pieces of writing and really open up Tam’s internal struggles. How did those evolve? Were they always part of your original outline, or did they materialize during the writing process?

Aunt Tigress started as idle writing exercises penned while traveling and vignettes of a magical childhood in Calgary, drawing quite heavily from exaggerated versions of my own experiences.

The mother-daughter relationships, especially, reflect my own conflicts and lovely moments with my mother. I am not just an introvert but a recovering agoraphobe terrified of talking on the phone, and I projected a lot of my insecurities onto Tam.

Earlier versions of Aunt Tigress saw flashback chapters alternating with present ones, and I genuinely believe it is the more competently written half of the novel.

It was the present-day plot that emerged during the writing process. Eventually, I decided I’d screwed Tam a little too much in her traumatic childhood and needed to write her a happy ending — she just had to earn it.

My first conception of Tam’s present-day story was a whimsical slice-of-life affair about a girl who inherits a magical shop and helps solve the problems of her supernatural community. I wrote chapters of her dealing with dandelion orphans, hermit angels that make wings out of garbage, and befriending the local gods — a novel for an alternate universe.

At the outset, Tam and Janet are navigating a new relationship. Can you give the readers a preview of the young couple’s struggles?

Everyone is tired of hearing that communication is key to relationships, but Tam needs to listen to it at least one more time. She’s partly a tiger with too little socializing, so that’s her excuse. Tam would rather relay a hundred stories about her supernatural lineage than express an opinion or pick what to eat for breakfast.

Throughout the novel, Tam and Janet run into issues around their different perspectives on sex. That’s a hard, intimidating conversation for asexual individuals like myself and an Elden Ring boss for someone like Tam.

Janet has no problems communicating, usually saying mature, therapist-approved words at appropriate times. However, she struggles with showing vulnerability and is indiscriminate with her snark.

The display of strength and confidence is a learned trait that came with her experiences coming out. Her blunt words and outbursts occasionally hurt those around her, and her social filter is a work in progress. Eventually, she needs a physical limitation to confront her fear of inadequacy and her doubts.